Shelli Markee is a silversmith, wire artist and (recently) a bassist. Working in her light-filled studio at home in Seattle, she wields a crème brûlée torch and melds imperfection with simplicity to create jewelry, art, and a beautiful life.

By Laura Lowery

“I was supposed to follow the bouncing ball and now I’m not,” she laughs.

I arrive to meet the artist Shelli Markee at her home studio and before I know it we are standing in her kitchen where everything new is old and she is pouring me a cold drink from a pitcher with teabags tied to a chopstick.

She lives and works in a relaxed Seattle craftsman she remodeled by reviving old treasures and building them right in—century-old cabinets with peeling paint, vintage stained glass, a scrubbed-white farmhouse sink.

Being in her home feels like being wrapped in a warm blanket, a quilt made of all the pieces I long for in my life: beauty, light, space, artistry, loving attention to detail. Every object feels good to see, smell, drink from, touch, gaze or sit upon.

We move to her art studio where blue French doors are flung open to a backyard garden with lavender and hummingbirds. I turn on my voice recorder as she smiles and tells me she is not a very wordy person. When corresponding with friends, even through text, she would rather take a photograph or draw a picture.

““I felt bad about that for a long time, not being able to express myself with words,” she confesses. “But I have a different way of doing things and now I feel more confident about that. That’s age.””

Shelli is beautiful, vibrant, with an earthy presence that feels light and clear. I quietly guess to myself she’s probably in her forties and, since she brought up age, I tell her I turned forty this year.

“Wow,” she nods. “That’s a big one. I came out when I was forty, it was a huge year.” Her eyes brighten and she goes on, “Now, at fifty-one, I feel the most myself and closest to the person I’m working towards.”

She’s fifty-one? This floors me.

“I want to focus on that eighty- year-old woman,” she continues. “I want to look back on my life and feel happy with the way I’ve lived, instead of thinking ‘I wish I had’ or ‘Why didn’t I?’”

Shelli is a silversmith and a wire artist. Her jewelry and artwork are known throughout the Pacific Northwest, where she shows and sells in artistic boutiques in Seattle, Portland, Edmunds, Bellevue, Issaquah and on Bainbridge Island.

“Both of my grandfathers were blacksmiths, but I didn’t start this work until I was forty.

“I’m sure technically being a silversmith is having and using the metal in a much broader sense. I solder and melt and bend. I do everything with crème brûlée torches. I don’t have big tanks. I don’t like power tools.”

Her first studio cost about two hundred dollars to set up. It was a nook in her kitchen, where she made a couple of earrings, some wire crowns for friends’ birthdays, and a wire bird.

“It started to become therapy when the boys went down to bed.”

Shelli and her former husband Brent are good friends now and co-parent their two teenaged sons. Brent is an industrial designer and she considers him an important mentor.

“He’s all about making it simple, bringing it back to its most basic.”

I see the influence of simplicity in Shelli’s work. Her jewelry evokes a sense of what is essential and unseen. Slight flaws in the hand-forged copper, silver and brass conjure vitality the way freckles bring an Irish face to life.

“When he gets an idea, he builds models first. All of his drafts create an arc that eventually curves back around to the original idea. Only then does he finally make the object and it’s perfect.

“He’s trying to have me make patterns too, but that takes too long. I’m like, are you kidding me? I’ve got to get into it and screw up the really nice material.”

““My mistakes are part of my process. They are even my product for awhile. Then if I tweak things, I get to an even better place.””

“If I did what Brent does and waited until the idea was ultimate, I wouldn’t create anything. It would take me forever. So it has to have the imperfection. I’m the most comfortable there.”

~

Halfway through our interview, I start to wonder if meeting her is some kind of message from the universe.

Turning forty this year brought an anxious feeling I haven’t been able to shake—that life’s possibilities are narrowing, that the decades defined by an abundance of choices are all behind me now.

Meeting Shelli felt like a new door opening through which I caught a glimpse of another future, one I had never noticed before—brilliant, gorgeous, graceful, even youthful—and full of potential.

~

Standing in the corner is a bass guitar she recently started learning to play. “I’m always obsessed with something. When the boys were young, it was gardening and I tried to get all my friends to do it with me. Now it’s playing bass.”

She rocks weekends as the newbie bassist in two Seattle bands.

“It’s so much noise! I don’t like lawnmowers, I don’t like fans, I can’t stand that noise. So it was surprising to find that I love playing bass. All the wires I’m tangled in, it’s a whole new outlet.

“I love practicing. There’s some satisfaction after I put in a couple hours and I’m so much better than I was two hours ago when I started. I get to sip on a beer, have a blast, and sometimes I’m like ‘Oh, man, I nailed that song!’ I like the process.”

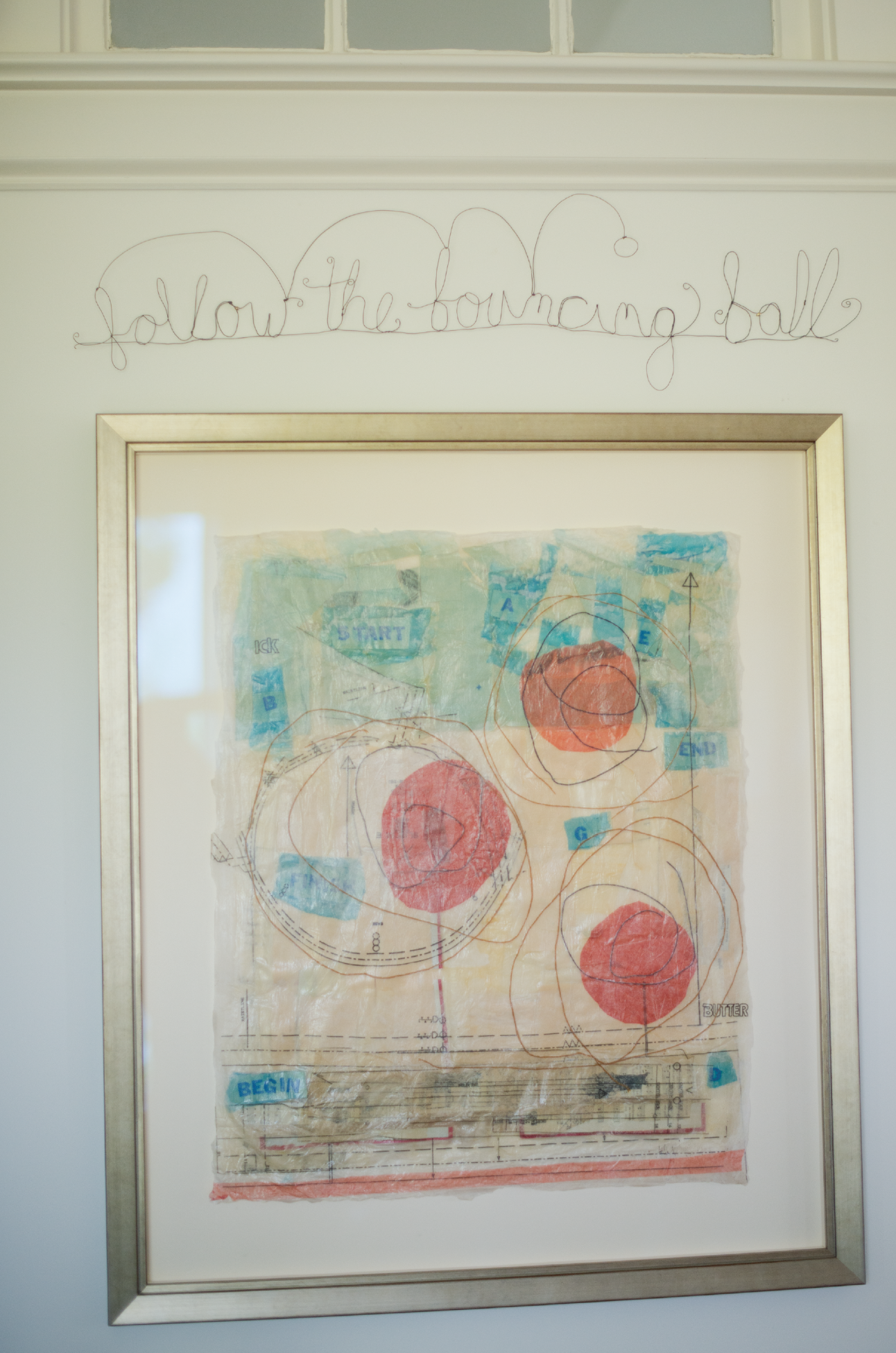

On the wall in her living room is a wire sculpture forming the words follow the bouncing ball, inspired by old Disney movie trailers where the audience is supposed to sing along as a little white ball bounces from word to word.

““It has a lot to do my upbringing. I was supposed to follow the bouncing ball and now I’m not,” she laughs. “I’ve been pulling away from that and becoming the person who I want to be and who I feel the most comfortable being.””

A self-portrait she painted sits on her bookshelf and she recounts how her father didn’t understand at first why she made herself look that way. He told her she is prettier than that.

“I don’t think of it as ugly or pretty,” she explains. “I think it’s light. He’s talking about these lines I painted on my face. Well, that’s me becoming comfortable with who I am. I’m not a Texas doll, although that’s how I started when I was younger. You know, makeup and shoes.”

She used to work in the fashion industry.

“Perfection in that world is so unrealistic,” she reflects. “We need to pull away from that and find beauty in age and wrinkles and gray hair. We need to have women as they age be honored as opposed to feeling like they should look twenty.”

As she speaks, window light surrounds her in a momentary halo and she appears lit from within. Softly edgy and unapologetically clear, her voice, like her artwork, seems to come from a well-tended internal fire.

“As I get older, I’m not comparing myself to what other people do as much. It’s been really fun to get to that place where I’m not being critical, I’m just doing what I like—and in that process there’s a lot of joy. I’m stepping away from what I’m supposed to be doing and doing my drive.”